What That Moment Must It Have Been Like

What that moment must have been like when General George Washington called his military leadership together. Tension filled the air. Knowing his men were cold, hungry and tired, clear thought was needed by the General. Knowing that hundreds of the men, whose time of service would soon be completed, and thus would be leaving the Continental Army at year's end on December 31, haste and speed were required. Only a very few days until then. Recent battles had been lost: Long Island, White Plains, Fort Washington; it was taking its toll on the Continental Army. The next loss might spell the end. The troops hadn’t been paid for several months. "As near as could be determined Washington had an army of about 7,500, but that was a paper figure only. Possibly 6,000 were fit for duty" (page 270, 1776 by David McCullough). Was there enough fight left in the troops to turn the tide against the oppressors? What to do, when, and how? Read this elegant prose by historian Ann Hawkes Hutton as she takes us inside the House of Decision.

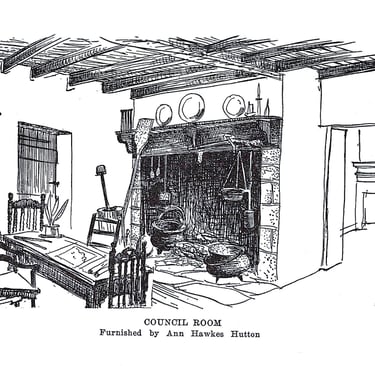

“A sentry leaned wearily against the tall red cedar near the front door of the Thompson-Neely House. He pulled his ragged coat up higher around his neck and sidled toward the south side of the tree for better protection against the biting December wind. By turning his head, he could still glance through the small panes of the one south window in the kitchen of the stone farmhouse. It was just past midnight and the firelight still glowed brightly in the room. Two figures were silhouetted in front of the fireplace. One was a tall, young man who made awkward nervous gestures as he paced before the fire. The other—middle-aged---was slumped in a chair next to a pile of maps and papers heaped on a long table. He had a handsome, heavily lined face and his fine features were drawn.

The young man was Lieutenant James Monroe, an eighteen-year-old Virginian, who did not dream that he would soon be a hero in the most significant battle of the American Revolution. Nor could he image that one day he would become the fifth president of the new nation for which he was fighting.

The older man was Lord Stirling—gentleman, astronomer, surveyor, soldier, and trusted friend of General Washington.

The sentry rubbed his numb hands together, then grabbed each elbow roughly in an effort to combat the cold. He wondered why the two inside the warm kitchen were still talking. All the other officers, who had crowded into the room during the evening, were gone—all except Washington. Instead of leaving with the others, the Commander-in-Chief had disappeared into the west wing of the house. ‘Must have stopped for a word with the sick,’ the sentry mused. But why was he staying so long? There were a number of questions in the sentry’s mind tonight. He had known something was afoot when he noticed a young officer carrying chairs from other rooms into the kitchen. He had guessed then that some sort of council of war would be held here. Extra sentries had been posted on the north of the farm as well as the river road and the top of Bowman’s Hill. An odd air of excitement had hovered about the house. Even the sick men in the west room seemed to sense it. The usual yelling and frequent oaths were muted. The only sound the sentry could hear was the pitiful retching of the patients lying on the matted straw.

Early in the evening the first officers had arrived—the men in charge of the river defenses—DeFernoy, Stephen, Sullivan, Cadwallader, Ewing, Knox, Starke, Glover, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Marshall too. Finally, the Commander-in-Chief himself appeared. Washington stopped, as always, in the `hospital’ room for a word of greeting to the sick before he entered the ‘great’ room—as the kitchen was called.

The sentry had watched the faces of the revolutionary leaders as the young officers carried still more chairs into the already crowded room. There was silence before Washington began to speak. The sentry could not hear what he was saying, but he could see the movement of his lips. The other officers were staring intently at their leader. Stirling was watching them—apparently anxious to see their reaction to Washington’s words.

What were they? The sentry had been wondering ever since the conference broke up more than an hour ago. He could not know that they were words which would launch the first great victory of the American Revolution. These walls of the Thompson-Neely House had been holding the most jealously guarded secret of the war—the crossing of the Delaware and surprise attack at Trenton. This stone farmhouse had been sheltering great men and great ideas and the two had combined to form a daring plan which would bring new life to a dying cause and new hope to all men everywhere who valued freedom.

The hour of decision had come to the Thompson-Neely House.”

(source: House of Decision, Ann Hawkes Hutton, Dorrance & Company, 1956, page 23-26)

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________